Euthanasia referendum: All you need to know about what your vote means

NZ Herald 25 April 2020

Family First Comment: “The safeguards are inadequate, the principle is unsound. And I think underneath all of this is a frightening fear of what it is to be disabled. People say ‘I don’t want to be wiped, I don’t want to drool, to be dependent. To me, that’s saying ‘I don’t want to be you’. I have a huge problem with that.”

#rejeactassistedsuicide

Protect.org.nz

What are the arguments against?

Many of the arguments against euthanasia also came from deeply personal experiences, including people with debilitating conditions who had recovered to live a long, fulfilling life.

One of the main concerns raised by opponents was that a law change would make disabled and elderly people more vulnerable. They could be pressured into ending their lives, possibly by family members who were exhausted by looking after them, fed up with the costs of care or medicine, or who wanted their inheritance earlier.

Older or disabled people could feel a “duty to die” because they believed they were a burden on their families.

Anti-euthanasia groups said it was simply not possible to safeguard against abuse or wrongful death. Protections which might seem strong in theory had never been tested by the realities of underfunded health systems or stressed families.

Governments could use assisted dying to save health costs. And euthanasia could worsen existing discrimination against poorer or Maori and Pacific families.

Another common argument was the slippery slope, which is mostly based on the experience in the Netherlands and Belgium, where euthanasia was extended to younger people after initially being limited to adults. Opponents say broader laws may not need Parliamentary approval, and instead could be gained through a court challenge.

There was concern about the absence of a stand-down period between first deciding to get euthanasia and when it can occur. “It would be possible for a person to receive a diagnosis of terminal illness on a Wednesday, gain the necessary approvals under the bill that same day, and be dead before the weekend,” said National MP Chris Penk, one of the bill’s most vocal opponents.

Some doctors objected to the change, saying it went against their core principle of not doing harm. They were also concerned about how difficult it was to accurately predict when a person might die, and the potential for misdiagnosis.

Some felt that the law change went against the Maori worldview, in which care and respect is shown for elderly and sick people and life and wairua are valued. Religious groups argued that life was sacred and that only God should decide life or death.

How does it compare to other countries?

New Zealand would become the sixth country in the world to legalise euthanasia or assisted dying. Several states in the United States and Victoria in Australia have also legalised.

New Zealand’s legislation is stricter than in the Netherlands and Belgium. The Netherlands allows people as young as 12 to request assisted dying, and it is available to non-terminal patients. Belgium has no age limit for children, but they must have a terminal illness to qualify.

Canada and the state of Victoria have similar regimes to New Zealand, limiting euthanasia to terminal people with six months to live – though Victoria extends that threshold to 12 months if the person has a degenerative neurological condition. Both Canada and Victoria also have stronger safeguards than New Zealand, because they require written confirmation from witnesses that a person is expressing their free will.

Victoria and some US states also have a “cooling off” period, or minimum time between a person deciding to die and when it can occur.

The Ministry of Justice has not done any analysis on how many people might apply for euthanasia if it were legalised. In a comparable jurisdiction, Victoria, demand far exceeded expectations. It was predicted that one person a month would choose to end their life, and since it has been introduced the rate has been closer to two a week.

‘THE SAFEGUARDS ARE INADEQUATE’

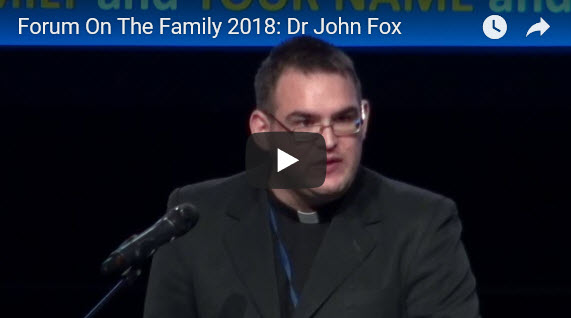

As an Anglican priest and disability advocate, Dr John Fox has been at a few deathbeds.

“I know what disabled life and disabled death looks like and the fairly severe sense of vulnerability that one has,” he said.

Fox, from Christchurch, will vote against the euthanasia referendum this year, saying it puts disabled people and others at risk.

“The safeguards are inadequate, the principle is unsound. And I think underneath all of this is a frightening fear of what it is to be disabled.

“People say ‘I don’t want to be wiped, I don’t want to drool, to be dependent. To me, that’s saying ‘I don’t want to be you’. I have a huge problem with that.”

The 37 year-old has a painful neuromuscular condition called spastic hemiplegia, and believes this would have qualified him for assisted dying under the originally drafted End of Life Choice Act. Eligibility for assisted dying in the legislation has now been narrowed to terminal patients with six months to live.

Fox said no matter how strict the safeguards were, legalising euthanasia meant that there was a fundamental shift to accepting that some lives were “not worth protecting”.

If the circumstances were extreme enough, anyone could understand why euthanasia could work in principle, he said.

“But we’re not talking about a thought experiment in a philosophy class. What we’re talking about is an actual category of people and it will be applied down at Middlemore Hospital in real life, in a place where funding is short, where there are bureaucrats and forms and power dynamics and difficulties.”

Even if he were not religious, he would oppose the bill on moral grounds.

“What I would ask people to think about is what disabled life and death is worth. My position is that if you wouldn’t do it to a rugby player, if you don’t do it to Dan Carter, you shouldn’t do it to me.”

READ MORE: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12318255 (behind paywall)