Bruce Logan – Board Member, Family First NZ

Bruce Logan – Board Member, Family First NZ

Like so many advocates for the End of Life Choice Bill, Labour MP Louisa Wall, while appealing to compassion, is infected by a confidence that she understands the mystery of human suffering (As on 9/11, choosing way you go is no sin – NZ Herald 13 Mar 2018).

Louisa Wall quotes the American academic Margaret Battin to defend her case. However, one wonders if Wall has carefully read the American academic’s complex and inconclusive work.

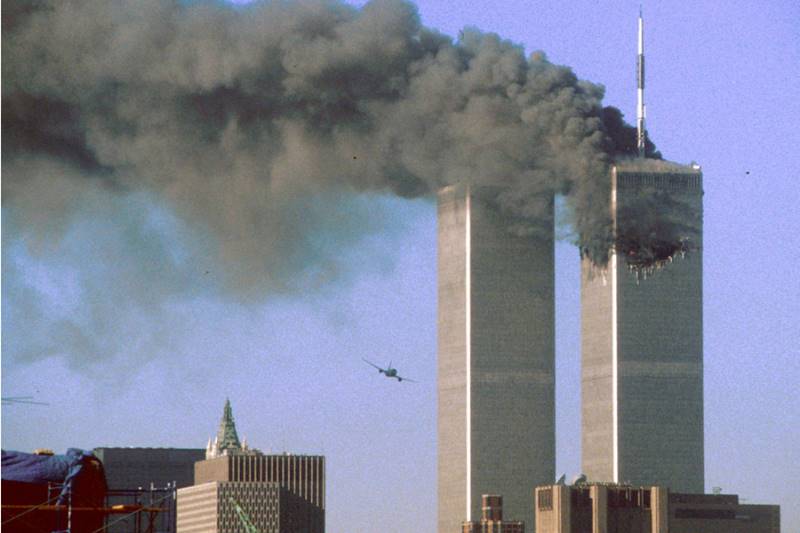

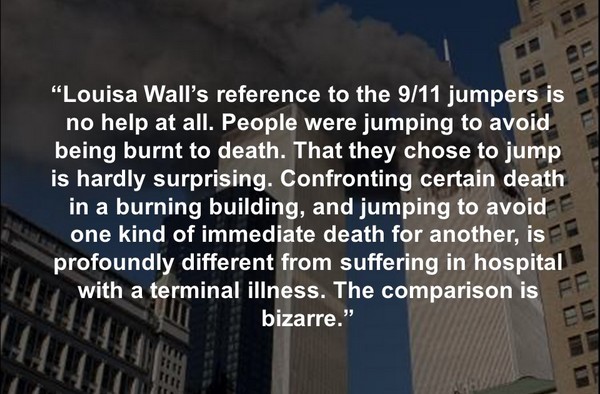

Louisa Wall’s reference to the 9/11 jumpers is no help at all. People were jumping to avoid being burnt to death. That they chose to jump is hardly surprising. Confronting certain death in a burning building and jumping to avoid one kind of immediate death for another is profoundly different from suffering in hospital with a terminal illness. The comparison is bizarre. This looks like a confused attempt to transfer sympathy for the jumpers to suicide generally and assisted suicide specifically. It’s beside the point.

Even if we accept the argument made by Battin and replicated by Wall, that we have a fundamental right to kill ourselves akin to the right to life, it does not follow that we should endorse the legalisation of physician assisted suicide, which is what the Bill demands.

Even if we accept the argument made by Battin and replicated by Wall, that we have a fundamental right to kill ourselves akin to the right to life, it does not follow that we should endorse the legalisation of physician assisted suicide, which is what the Bill demands.

Implicit in all the arguments for the End of Life Choice Bill is the befuddled human rights ideology informed by utilitarianism.

Life, according to this ideology, is about human usefulness, a usefulness that can be understood and circumscribed by legislation. Reference to “quality of life” turns up ad nauseam. The phrase is used with unqualified confidence as though the users know what it means. But they don’t. Unless they have insight into the mystery of life not available to the rest of us.

Louisa Wall says she believes “…we need to create a state authorised mechanism to enable death for those who have been diagnosed with an incurable medical condition that becomes terminal when all state treatments have been exhausted, and the person, based on medical knowledge, has less than 12 months to live.” That sounds like something out of Huxley’s Brave New World or George Orwell’s 1984.

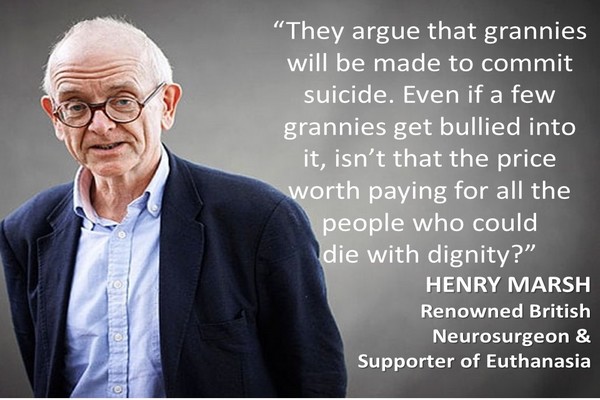

It is this kind of faith in a clinical diagnosis that can readily encourage a duty to die. Age rationing, a “just” distribution of health care income is likely to become a compulsory consideration. Spending money on the elderly is inefficient. The young will benefit more.

The logic of physician assisted suicide must lead to doctors, and worse, corporate administrators deciding which lives are worth saving, caring for, and those who would be better off dead. The administrators’ decisions will not be based on compassion. They will be made by the strong over the weak. In passing, Stephen Hawking was diagnosed with Motor Neurone disease and given 2 years to live. Had assisted suicide been legal we might not have had him.

By legalising assisted suicide we undermine the outworking of compassion. Compassion is a virtue and it comes at a cost. To suffer alongside someone we love is painful. But both the sufferer and the comforter know they are doing something of great value. It enriches the life of both. Compassion reinforces trust and encourages hope. The value and mystery of the human journey is less likely to be devalued.

Conversely physician assisted suicide diminishes trust between the patient, relatives and friends, and in the profession generally. Suffering is not resolved, but potentially transferred to the lives of the relatives and even the physician. Whoever participates in assisted suicide assumes a unique responsibility for the act of ending a person’s life. He or she will never be sure that they had done the right thing. Guilt will remain a possible, even likely accuser.

Conversely physician assisted suicide diminishes trust between the patient, relatives and friends, and in the profession generally. Suffering is not resolved, but potentially transferred to the lives of the relatives and even the physician. Whoever participates in assisted suicide assumes a unique responsibility for the act of ending a person’s life. He or she will never be sure that they had done the right thing. Guilt will remain a possible, even likely accuser.

When a loved one is dying, resolution, forgiveness and shared declarations of love and hope between the comforter and sufferer is deeply human. Trust is essential. Such trust becomes very difficult to achieve if legalised assisted suicide is lurking in the wings. Sure, pain is a serious problem in some cases, but it is frequently inconsistent and can cause us to make decisions we later regret.

Those who demand the legalisation of assisted suicide fail to understand the critical difference between pity and compassion. It is pity that demands the end of pain as quickly as possible. Compassion weeps with pity but sees further. Pity believes that suffering is the greatest evil. Compassion understands suffering’s terror as it tries to come to grips with the death of a loved one.

The legalisation of assisted suicide solves no problems at all. It does nothing to reduce pain or help us confront the reality of death. Indeed, it is more likely to turn dying into what the utilitarians have always wanted, disposal of the useless.