Disturbing Data In Latest “Assisted Dying” Report

Media Release: 5 September 2024

The latest review of assisted suicide / euthanasia was quietly released last month by the Ministry of Health – but it should sound significant and loud warning bells about the law, especially at a time when proponents want it to be liberalised even further.

Family First has analysed the Registrar (assisted dying) Annual Report June 2024. Key findings include:

- 5% increase in assisted deaths in the last 12 months. [2022 66 (5 mnths), 2023 328, 2024 344]

- 11% increase in applications.

- 83% NZ European/Pākehā. Pasifika <0.5%. Māori <4%. Asian 2%. Other 12%.

- 60% aged 65-84. 19% 85+. 19% 45-64.

- Virtually even split between male and female.

- 12% of applicants had a disability.

- 258 applicants died before ‘needing’ euthanasia.

- The application process averages only 16 days.

- Less than 7% of applicants are for neurological conditions (such as Huntington’s Disease).

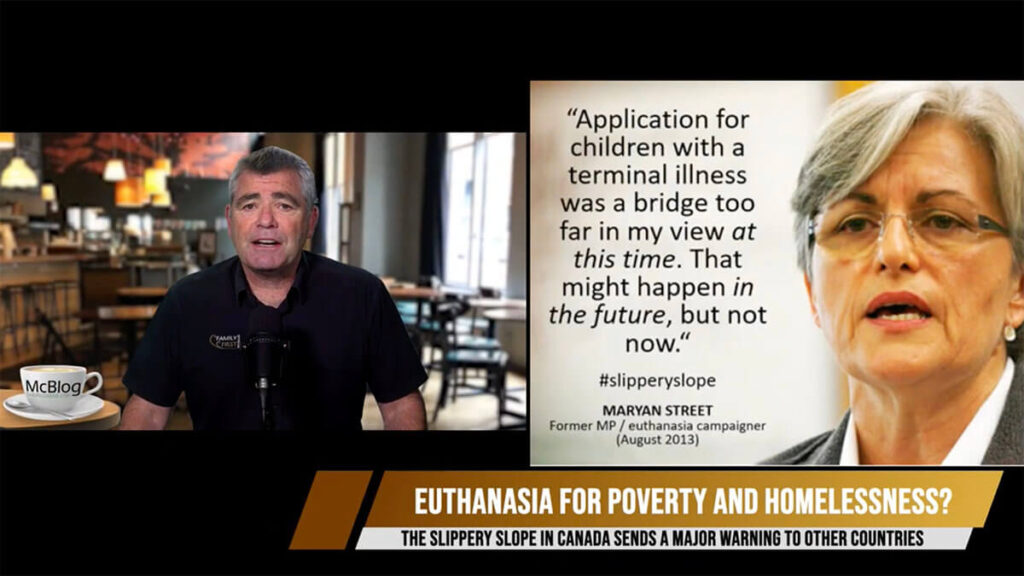

What is most disturbing is that one in four applicants weren’t receiving palliative care. The End of Life Choice Act only provides a ‘right’ to one choice – premature death. There is no corresponding right to palliative care. Good palliative care and hospice services are resource intensive; euthanasia would be cheaper. As has also been observed overseas, notably in Canada, there is a new element of ‘financial calculation’ into decisions about end-of-life care. This is harsh reality. At an individual level, the economically disadvantaged who don’t have access to better healthcare could feel pressured to end their lives because of the cost factor or because other better choices are not available to them. Some hospitals have no specialist palliative care services at all.

The NZ Herald recently reported: “A specialist paediatric palliative care (PPC) doctor says New Zealand is falling behind other nations in its care of terminally ill children and the Government must step up to help.” And the demand for this specialist medical care will only increase significantly in the near future. Our population is ageing, and therefore the number of people requiring palliative care is forecast to increase by approximately 25% over the next 15 years and will be more than double that by 2061.

Previous Governments have made little effort to address this growing problem and to increase funding for palliative care, and essential service. Euthanasia is instead given priority and full Government funding.

The other significant red flag in the report is that just 1% of applicants had a psychiatric assessment to check for both competence to make the decision, and for any presence of coercion. 99% of applicants were not assessed for these.

That so few patients are referred raises serious questions around the competency of doctors involved in euthanasia, and also implies either key psychological signs are being ignored – or missed.

Many patients who are facing death or battling an irreversible, debilitating disease are depressed at some point. However, many people with depression who request euthanasia overseas revoke that request if their depression and pain are satisfactorily treated. If euthanasia or assisted suicide is approved, many patients who would have otherwise traversed this dark, difficult phase and gone on to find meaning in their remaining months of life will die prematurely.

The unspoken reality is also that terminally ill people are vulnerable to direct and indirect pressure from family, caregivers and medical professionals, as well as self-imposed pressure. They may come to feel euthanasia would be ‘the right thing to do’; they’ve ‘had a good innings’ and do not want to be a ‘burden’ to their nearest and dearest. It is virtually impossible to detect subtle emotional coercion, let alone overt coercion, at the best of times.

This latest data simply confirms that nothing in the law guarantees the protection required for vulnerable people facing their death, including the disabled, elderly, depressed or anxious, and those who feel themselves to be a burden or who are under financial pressure.

Family First is also deeply concerned by comments by Associate Minister of Health David Seymour who is overseeing the review of the law. He recently stated on RNZ:

“The statutory review is being the Ministry of Health right now. I believe, without pre-empting what it will say, that it will give a lot of weight to making change.”

It is deeply disturbing that a Minister would campaign and potentially unduly influence an independent review with this type of commentary.

It’s time we focused on and fully funded world-class palliative care – and not a lethal injection.

We can live without euthanasia.

DOWNLOAD OUR FACT SHEET ON THE LAW https://familyfirst.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Euthanasia-Fact-Sheet.pdf