20 Reasons To Vote NO

Translations of this Pamphlet are now available. CLICK HERE.

1. We already have choice

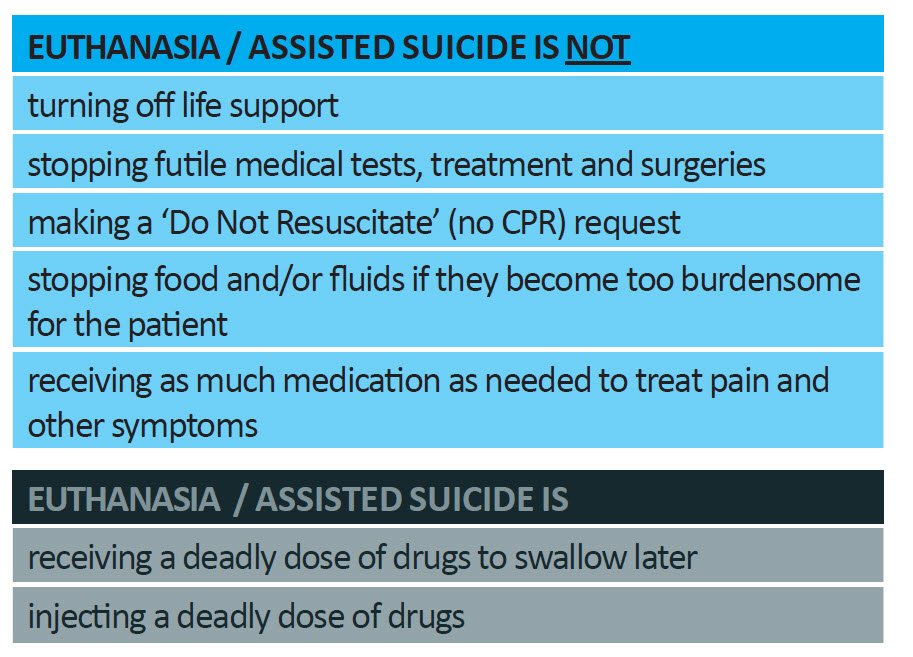

A person may refuse medical treatment, even if it will result in his or her death.[5] Section 11 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 says, “Everyone has the right to refuse to undergo any medical treatment.” This can include ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ orders. Refusing medical treatment is not euthanasia. The Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine (ANZSPM 2013) states:

“Patients have the right to refuse life sustaining treatments including the provision of medically assisted nutrition and/or hydration. Refusing such treatment does not constitute euthanasia.”

It’s really important to understand the terminology in this debate. Most people simply want to ensure that the administration of pain relief and the withdrawal of burdensome treatment are not treated as illegal. That’s already the case. There is no legal or ethical requirement that a diseased or injured person must be kept alive ‘at all costs’. The law has drawn a clear and consistent line between withdrawing medical support thereby allowing the patient to die of his or her own medical condition, versus intentionally bringing about the patient’s death.

It’s really important to understand the terminology in this debate. Most people simply want to ensure that the administration of pain relief and the withdrawal of burdensome treatment are not treated as illegal. That’s already the case. There is no legal or ethical requirement that a diseased or injured person must be kept alive ‘at all costs’. The law has drawn a clear and consistent line between withdrawing medical support thereby allowing the patient to die of his or her own medical condition, versus intentionally bringing about the patient’s death.

Voluntary Euthanasia is the act of intentionally, knowingly, and directly causing the death of a patient, at the request of the patient. If someone other than the person who dies performs the last act, euthanasia has occurred.[1] Involuntary Euthanasia is where the person is able to give consent but has not done so, or where a person was euthanised against their will. Non-voluntary Euthanasia is where the person lacks capacity to give consent or request to end his or her life.[2]

Assisted Suicide is the act of intentionally and knowingly providing the means of death to another person at that person’s request in order to facilitate his/her suicide. If the person who dies performs the fatal act, assisted suicide has occurred.[3]

Physician (doctor)–assisted suicide is where the person providing the means (e.g. lethal drugs) is a medical practitioner.

Assisted dying is a term that is also used for both euthanasia and assisted suicide.

NOTE:

The End of Life Choice Act 2019 allows both euthanasia and assisted suicide. It would allow doctors and nurse practitioners to provide or administer a lethal dose of drugs.

In contrast, Palliative care is

“active total care… for people whose illness is no longer curable, the goal is around providing quality of life, managing pain and symptoms to enable people to live every moment in whatever way is important to them.” (Hospice NZ)

What is not euthanasia

The administration of pain relief

Everyone has a right to effective pain relief. The administration of drugs in doses sufficient to alleviate pain and suffering rarely causes death. It is permitted, and it is ethical. From time to time, a patient may die while receiving such drugs. That is not euthanasia, since the death of the patient was not the intended outcome of the medication. The Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine (ANZSPM 2013) states: “Treatment that is appropriately titrated to relieve symptoms and has a secondary and unintended consequence of hastening death, is not euthanasia.” (our emphasis added) (“Titrated” means measured and adjusted).

The withdrawal of burdensome and futile life-prolonging treatment

The common practice of withdrawing futile medical assistance from a patient for whom it is not accomplishing anything useful, despite this action being associated potentially with the person’s death, is lawful. There is no legal or ethical requirement that a diseased or injured person must be kept alive ‘at all costs’. The law has drawn a clear and consistent line between withdrawing medical support, thereby allowing the patient to die of his or her own medical condition, and intentionally bringing about the patient’s death by a positive act.[4]

What does the law currently say about suicide

Section 179 of the Crimes Act 1961 (NZ) states that “Everyone is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 14 years who—(a) incites, counsels, or procures any person to commit suicide, if that person commits or attempts to commit suicide in consequence thereof; or (b) aids or abets any person in the commission of suicide.” Furthermore, under s 151 there is a duty to provide the “necessaries” of life to those who have the care or charge of a “vulnerable adult” who is unable to provide himself or herself with these essentials.

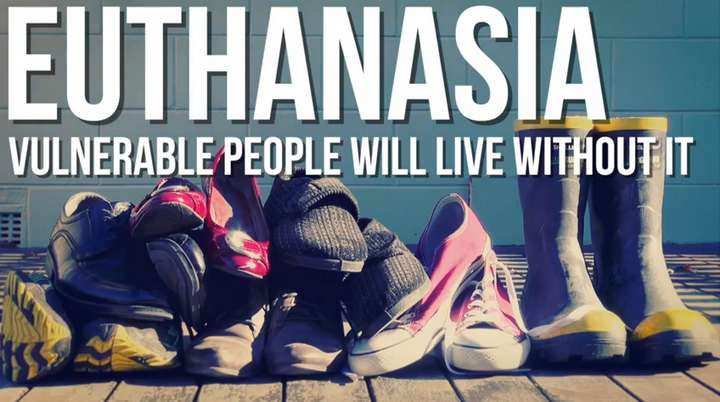

2. Abuse will happen

The terminally ill and those living with life-limiting illnesses are often vulnerable. And not all families, whose interests are at stake, are wholly unselfish and loving. They could coerce a patient into requesting euthanasia, perhaps to get an inheritance sooner or to save themselves the ‘burden’of caring for the patient. An overseas study found that a third of all euthanasia deaths in the Flemish region of Belgium are done without explicit request[6] and the legal requirement to report euthanasia has not been fully complied with in other countries that allow euthanasia either. Vulnerable people may be persuaded that they want to die or that they ought to want to die.[7] We need to apply the precautionary principle: the higher the risk – the higher the burden of proof on those proposing legislation. The risk of abuse cannot be eliminated. ‘Safe’ euthanasia is an illusion.

The terminally ill and those living with life-limiting illnesses are often vulnerable. And not all families, whose interests are at stake, are wholly unselfish and loving. They could coerce a patient into requesting euthanasia, perhaps to get an inheritance sooner or to save themselves the ‘burden’of caring for the patient. An overseas study found that a third of all euthanasia deaths in the Flemish region of Belgium are done without explicit request[6] and the legal requirement to report euthanasia has not been fully complied with in other countries that allow euthanasia either. Vulnerable people may be persuaded that they want to die or that they ought to want to die.[7] We need to apply the precautionary principle: the higher the risk – the higher the burden of proof on those proposing legislation. The risk of abuse cannot be eliminated. ‘Safe’ euthanasia is an illusion.

The End of Life Choice Act is seriously deficient in so far as it only requires doctors to “do their best” to ensure that the person is free from pressure – an extremely low legal threshold. Moreover, it fails to outline any process for ensuring patients are free from coercion. As the NZMA stated in their submission to the Justice Select Committee: “The provisions in the Bill will not ensure that a decision to seek assisted dying will always be made freely and without subtle coercion.” In addition, a euthanasia request could be signed on a person’s behalf by someone who stands to benefit from that person’s death. [The majority of MPs voted against strengthening safeguards in this area SOP 306].

3. Diagnosis and prognosis can be wrong

Diagnosis and prognosis are based on probability, not certainty. Some people will be euthanised on account of a disease they thought they had but did not. The Act that we are voting on relies on a diagnosis that a person suffers from a terminal illness which is “likely” to end his or her life within six months. There are many examples of individuals who have outlived their prognoses – sometimes by months, even years. A diverse range of research into this issue over the past several decades suggests that the diagnosis is wrong 10–15% of the time.[8] A 2012 paper published in the British Medical Journal noted that 28% of autopsies report at least one misdiagnosis[9]. A study of doctors’ prognoses (the medical prediction of the course of a disease over time) for terminally Ill patients found only 20% of predictions were within 33% of the actual survival time[10].

Diagnosis and prognosis are based on probability, not certainty. Some people will be euthanised on account of a disease they thought they had but did not. The Act that we are voting on relies on a diagnosis that a person suffers from a terminal illness which is “likely” to end his or her life within six months. There are many examples of individuals who have outlived their prognoses – sometimes by months, even years. A diverse range of research into this issue over the past several decades suggests that the diagnosis is wrong 10–15% of the time.[8] A 2012 paper published in the British Medical Journal noted that 28% of autopsies report at least one misdiagnosis[9]. A study of doctors’ prognoses (the medical prediction of the course of a disease over time) for terminally Ill patients found only 20% of predictions were within 33% of the actual survival time[10].

Victoria Reggie Kennedy, widow of the late Democratic Senator Edward Kennedy, campaigned against a bill that would have legalised physician-assisted suicide in Massachusetts. She said:

“When my husband was first diagnosed with cancer, he was told that he had only two to four months to live, that he’d never go back to the U.S. Senate, that he should get his affairs in order, kiss his wife, love his family and get ready to die. But that prognosis was wrong. Teddy lived 15 more productive months.… Because that first dire prediction of life expectancy was wrong, I have 15 months of cherished memories – memories of family dinners and songfests with our children and grandchildren; memories of laughter and, yes, tears; memories of life that neither I nor my husband would have traded for anything in the world. When the end finally did come – natural death with dignity – my husband was home, attended by his doctor, surrounded by family and our priest.”[11]

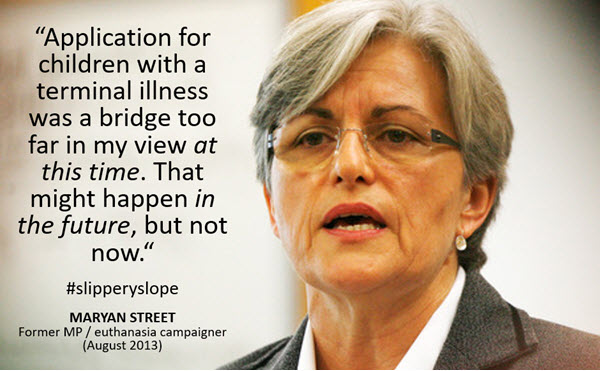

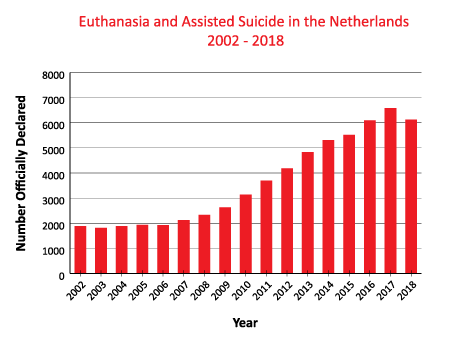

4. A slippery slope

There is concrete evidence from the countries which have introduced euthanasia that the availability and application of euthanasia expands to situations not initially envisaged. When a newly-permitted activity is characterised as a ‘human right’, the overseas experience is that there is inevitably a push to extend such a ‘right’ to a greater number of people, such as those with chronic conditions. disabilities, mental illness, those simply ‘tired of life’, or even children.

There is concrete evidence from the countries which have introduced euthanasia that the availability and application of euthanasia expands to situations not initially envisaged. When a newly-permitted activity is characterised as a ‘human right’, the overseas experience is that there is inevitably a push to extend such a ‘right’ to a greater number of people, such as those with chronic conditions. disabilities, mental illness, those simply ‘tired of life’, or even children.

Euthanasia became legal in the Netherlands in 2002. It allows euthanasia for those aged at least 12 years of age.[12] Children aged from 12 – 15 years require parental consent. More recently, some Dutch doctors are urging lawmakers to extend the euthanasia law to include children aged 1 to 12.[13] Belgium, which introduced euthanasia for those at least 18 years of age in 2002, voted to extend the practice to children in 2014.[14]

Professor Theo Boer was a member of the Dutch Regional Euthanasia Commission for nine years, during which he was involved in reviewing 4,000 cases. He was a strong supporter of euthanasia and argued originally that there was no ‘slippery slope’. However, by 2014 he had had a complete change of mind. He testified to UK politicians considering the issue:

“Whereas in the first years after 2002 hardly any patients with psychiatric illnesses or dementia appear in reports, these numbers are now sharply on the rise. Cases have been reported in which a large part of the suffering of those given euthanasia or assisted suicide consisted in being aged, lonely or bereaved. Some of these patients could have lived for years or decades.”[15]

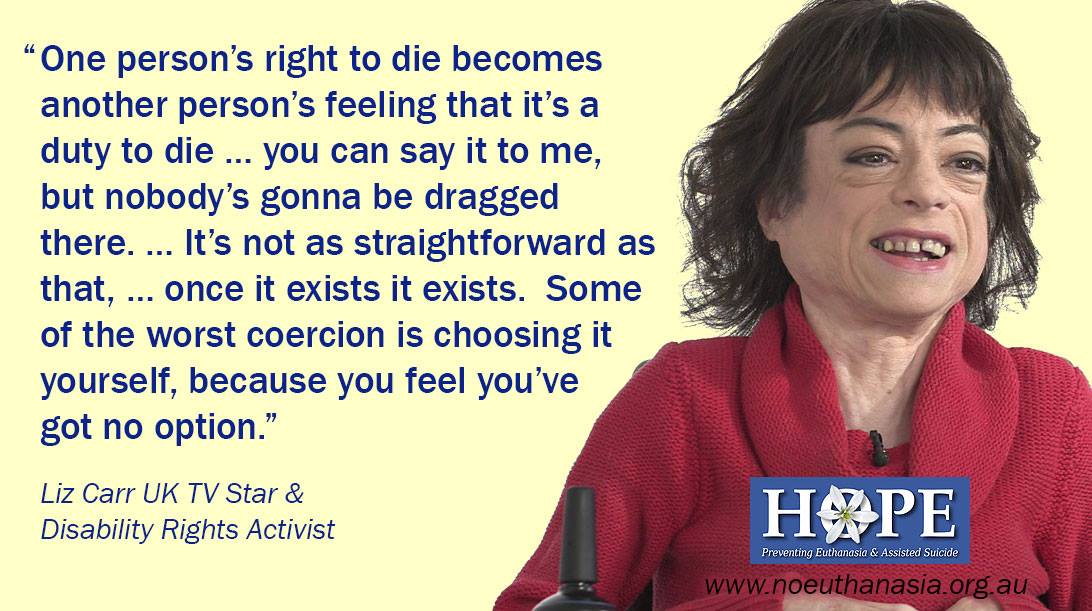

5. ‘Right to die’ will become a ‘duty to die’

Coercion is subtle. The reality is that terminally ill people are vulnerable to direct and indirect pressure from family, caregivers, and medical professionals, as well as self-imposed pressure. They may come to feel euthanasia would be ‘the right thing to do’; they’ve ‘had a good innings’ and do not want to be a ‘burden’ to their nearest and dearest. Talk to any doctor and they will tell you it is virtually impossible to detect subtle emotional coercion, let alone overt coercion, at the best of times.

Coercion is subtle. The reality is that terminally ill people are vulnerable to direct and indirect pressure from family, caregivers, and medical professionals, as well as self-imposed pressure. They may come to feel euthanasia would be ‘the right thing to do’; they’ve ‘had a good innings’ and do not want to be a ‘burden’ to their nearest and dearest. Talk to any doctor and they will tell you it is virtually impossible to detect subtle emotional coercion, let alone overt coercion, at the best of times.

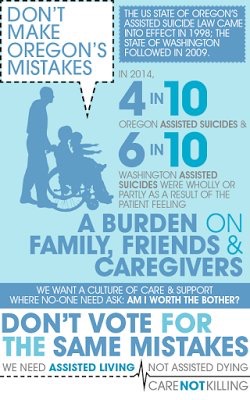

Annual reports by Oregon Public Health contain data on the numbers of patients who reported that part of their motivation to request euthanasia was because they felt themselves to be a “burden on family and friends”.[16] 49 percent of patients who requested assisted suicide in 2016 did so out of concern for being a burden on their family; only 13% did so in 1998.

6. Increased risk of elder abuse

Elder abuse is already a significant problem in New Zealand. About 80% of it remains hidden and unreported. We cannot ignore the possibility that dependent elderly people may be coerced into assisted suicide/euthanasia. Elderly and ailing patients are also all too aware that their increasingly expensive rest home and geriatric care is steadily dissipating the inheritance that awaits their children. Sadly, some unscrupulous and callous offspring might not be slow in pointing this out.

Elder abuse is already a significant problem in New Zealand. About 80% of it remains hidden and unreported. We cannot ignore the possibility that dependent elderly people may be coerced into assisted suicide/euthanasia. Elderly and ailing patients are also all too aware that their increasingly expensive rest home and geriatric care is steadily dissipating the inheritance that awaits their children. Sadly, some unscrupulous and callous offspring might not be slow in pointing this out.

Emeritus Professor David Richmond contends:

“It is older people (and those with disabilities, of whom older people form a large percentage) who actually have the most to fear from legalising these practices…. Older people are, by and large, very sensitive to being thought to be a burden, and more likely than a young person to accede to more or less subtle suggestions that they have “had a good innings.”… That is why most District Health Boards in the country have an Elder Abuse team. Hence subtle and not so subtle pressure on older people to request euthanasia where it is available as an option for medical “care” is not always because the family has the best interests oftheir ageing relative at heart.”[17]

7. Assisting suicide may promote suicide

As 21 mental health practitioners and academics recently argued, there is mounting statistical evidence from Oregon, Belgium and the Netherlands that as the numbers using assisted dying rise, so too do suicide rates in the general population. It may be that promoting suicide as a response to suffering is a message that cannot be contained to just those with a terminal illness. Proponents of the Act that we are voting on have been asked to prove that legalising assisted suicide won’t raise the general suicide rate, but they won’t because they can’t. On the one hand society will offer some individuals assistance to commit suicide, i.e. euthanasia, yet on the other hand seek to prevent individual suicides. Given our suicide epidemic, sensible and caring thinking says it is too risky to proceed.

As 21 mental health practitioners and academics recently argued, there is mounting statistical evidence from Oregon, Belgium and the Netherlands that as the numbers using assisted dying rise, so too do suicide rates in the general population. It may be that promoting suicide as a response to suffering is a message that cannot be contained to just those with a terminal illness. Proponents of the Act that we are voting on have been asked to prove that legalising assisted suicide won’t raise the general suicide rate, but they won’t because they can’t. On the one hand society will offer some individuals assistance to commit suicide, i.e. euthanasia, yet on the other hand seek to prevent individual suicides. Given our suicide epidemic, sensible and caring thinking says it is too risky to proceed.

Research on human decision-making suggests that when a person is suffering, decision-making becomes less rational.[18] Most of the demands for legalising euthanasia and assisted suicide come from strong-minded individuals who are intelligent, articulate and who clearly comprehend their predicament. But many people are not like that. Yet a euthanasia law will have to protect everyone – the inarticulate as well as the articulate, the impaired, gullible or naïve, as well as the intelligent and alert.[19]

The recent government report on euthanasia (2017) said:

“Many submitters were concerned that if assisted dying was legalized, people would see death as an acceptable response to suffering. It would be difficult to say that some situations warranted ending one’s life while others do not. These submitters were concerned that while terminal illnesses would initially be the only scenario in which ending one’s life would be considered acceptable, this would quickly widen to include any degree of physical pain, then to include mental pain, and then in response to many other situations that arise throughout life… Several submitters suggested that, during their worst periods of depression, they would have opted for euthanasia had it been available in New Zealand.”

Advocates of assisted suicide tried to suggest that suicide can be categorised as either ‘rational’ or ‘irrational’. But the government report also said:

“This distinction was not supported by any submitters working in the field of suicide prevention or grief counselling. On the contrary, we heard from youth counsellors and youth suicide prevention organisations that suicide is always undertaken in response to some form of suffering, whether that is physical, emotional, or mental.”

8. Depression may be influencing the decision

Virtually all patients who are facing death or battling an irreversible, debilitating disease are depressed at some point. However, many people with depression who request euthanasia overseas revoke that request if their depression and pain are satisfactorily treated.[22] Even very mild depression – of the kind that would not render a person legally incompetent – can have a marked effect on one’s predisposition to live or die. If euthanasia or assisted suicide is allowed, many patients who would have otherwise traversed this dark difficult phase and gone on to find meaning in continued living may not get that chance and will die prematurely.

Virtually all patients who are facing death or battling an irreversible, debilitating disease are depressed at some point. However, many people with depression who request euthanasia overseas revoke that request if their depression and pain are satisfactorily treated.[22] Even very mild depression – of the kind that would not render a person legally incompetent – can have a marked effect on one’s predisposition to live or die. If euthanasia or assisted suicide is allowed, many patients who would have otherwise traversed this dark difficult phase and gone on to find meaning in continued living may not get that chance and will die prematurely.

9. Assisted suicide devalues the disabled

Advocates for the rights of people with disabilities are correct to be concerned. New Zealander Dr John Fox, a sufferer of spastic hemiplegia who is in daily pain, says:

“Don’t drop us. Don’t make it harder for us. Don’t tempt us to end our lives. When we have our darkest moments, we need our country to reflect back to us that we are loved, necessary, valued and equal. Even though they say they’ve fixed [the Act], we know that a law like this broadens, that we can’t control it, that loopholes come back to haunt us. That’s why [David] Seymour’s Bill is dangerous.”

As disability rights group Not Dead Yet put it, “There are endless ways of telling disabled people time and time again that their life has no value.”[23]

The vast majority of euthanasia/assisted suicide deaths are made on the basis of disability, not because a person is in pain. This is backed by the Oregon statistics that show 90% say they requested assisted suicide because they were “less able to engage in activities making life enjoyable” and 87% said they were requesting because they were “losing autonomy” – compared to 33% who indicated that they were requesting to die because of pain or concern about pain.

Baroness Campbell of Surbiton, former Commissioner of the Equality and Human Rights Commission and of the Disability Rights Commission, who has spinal muscular dystrophy has argued in the UK House of Lords: “…The Bill offers no comfort to me. It frightens me because, in periods of greatest difficulty, I know that I might be tempted to use it. It only adds to the burdens and challenges which life holds for me”.[24]

Baroness Campbell of Surbiton, former Commissioner of the Equality and Human Rights Commission and of the Disability Rights Commission, who has spinal muscular dystrophy has argued in the UK House of Lords: “…The Bill offers no comfort to me. It frightens me because, in periods of greatest difficulty, I know that I might be tempted to use it. It only adds to the burdens and challenges which life holds for me”.[24]

There are many examples.[25] In December 2012, Marc and Eddy Verbessem, 45-year-old deaf twins, were euthanised in a Belgian hospital after they discovered they were going blind.[26] Nancy Verhelst, a 44-year-old transsexual Belgian whose doctors made mistakes in three sex change operations, was left feeling as though she was a “monster.” She then requested—and was granted—euthanasia by lethal injection.[27] In the Netherlands, the euthanized include Ann G., a 44-year-old woman whose only ailment was chronic anorexia.[28] In the beginning of 2013, Dutch doctors administered a lethal injection to a 70-year-old blind woman because she said the loss of sight constituted “unbearable suffering.”[29] In early 2015, a 47-year-old divorced mother of two suffering from tinnitus, a loud ringing in the ears, was granted physician-assisted suicide in the Netherlands.[30] She left behind a 13-year-old son and a 15-year-old daughter. Gerty Casteelen was a 54-year-old psychiatric patient with molysomophobia, a fear of dirt or contamination. Her doctors decided that she would not be able to control her fear and agreed to administer a lethal injection.[31]

10. Cost may drive critical decisions

The End of Life Choice Act 2019 only provides a ‘right’ to one choice – premature death. There is no corresponding ‘right’ to palliative care. Good palliative care and hospice services are resource intensive; euthanasia would be cheaper. A law change will introduce a new element of ‘financial calculation’ into decisions about end-of-life care. This harsh reality is arguably the ‘elephant in the room’ in the debate. At an individual level, the economically disadvantaged who don’t have access to better healthcare could feel pressured to end their lives because of the cost factor or because other better choices are not available to them.

The End of Life Choice Act 2019 only provides a ‘right’ to one choice – premature death. There is no corresponding ‘right’ to palliative care. Good palliative care and hospice services are resource intensive; euthanasia would be cheaper. A law change will introduce a new element of ‘financial calculation’ into decisions about end-of-life care. This harsh reality is arguably the ‘elephant in the room’ in the debate. At an individual level, the economically disadvantaged who don’t have access to better healthcare could feel pressured to end their lives because of the cost factor or because other better choices are not available to them.

In Canada, it has been estimated that euthanasia and assisted suicide will reduce annual health care spending by between $34.7 million and $138.8 million (CA$).[33] The very existence of this report highlights the frightening prospect that money and markets are likely to influence the scope and reach of euthanasia and assisted suicide in the event that it was ever legalised in New Zealand. In 2008, two patients from Oregon who were on Medicaid – ‘the state’s health insurance plan for the poor’ – were denied state-sponsored treatment but told the state would pay for assisted suicide.[34] The cold fiscal reality is that, “end of life care is expensive and having citizens opt for an earlier death is associated with substantial government savings”.[35]

There is also growing evidence from Canada and the US that people are choosing euthanasia or assisted suicide because of a lack of access to proper end-of-life care – in other words because of a lack of real choice. This will especially affect people in lower socio-economic areas.

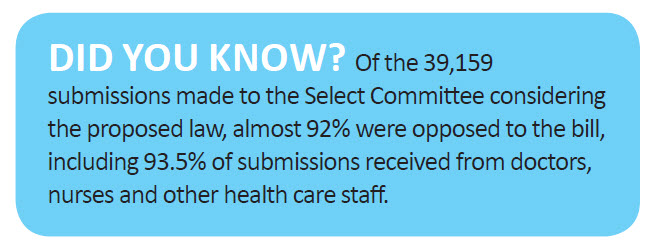

11. Widespread opposition from people who know

Opposition to the Act that we are voting on has come from those in the disability sector, senior citizens, human rights advocates, lawyers, doctors and others in the health sector.

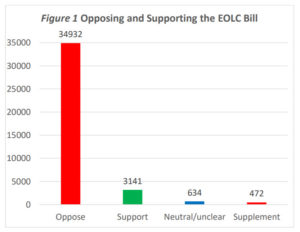

Source: Care Alliance analysis

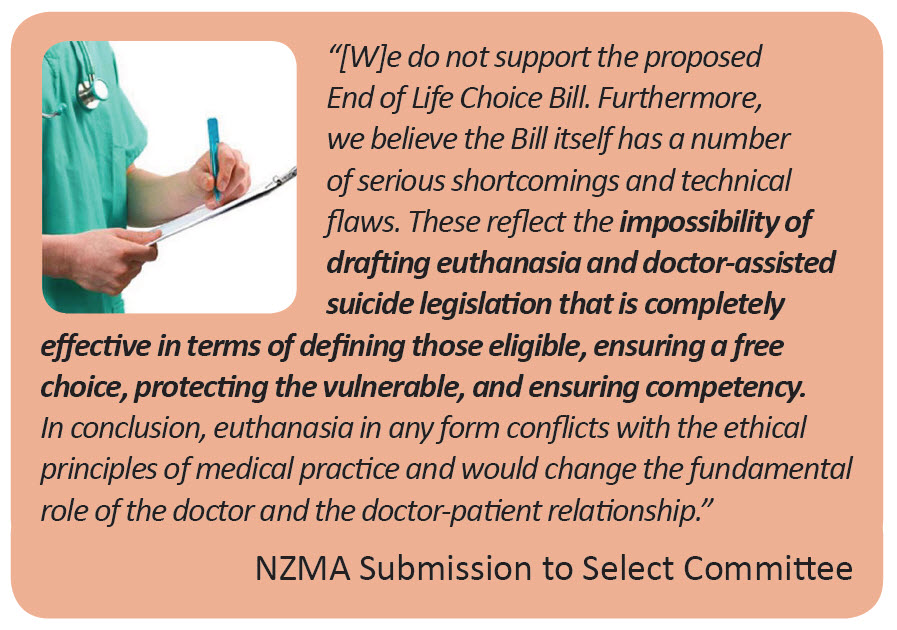

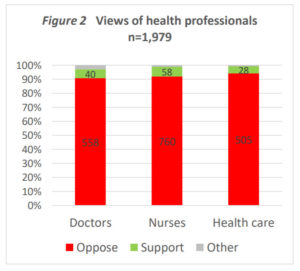

12. Medical bodies oppose it

The majority of the medical profession and national medical associations around the world remain resolutely opposed to the introduction of euthanasia or assisted suicide.[36]

The majority of the medical profession and national medical associations around the world remain resolutely opposed to the introduction of euthanasia or assisted suicide.[36]

In the New Zealand Medical Association’s submission to the Select Committee considering the End Of Life Choice Bill, they said:

“The New Zealand Medical Association (NZMA) has clearly stated its opposition to euthanasia and doctor-assisted suicide, and regard these practices to be “unethical and harmful to individuals, especially vulnerable people, and society.”[37]

The World Medical Association Resolution on Euthanasia, representing more than 10 million physicians worldwide, “strongly encourages all National Medical Associations and physicians to refrain from participating in euthanasia, even if national law allows it or decriminalizes it under certain conditions.”[38] The Australia and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine (ANZSPM) Position Statement on Euthanasia (2017) states: “In accordance with best practice guidelines internationally, the discipline of Palliative Medicine does not include the practices of euthanasia or physician assisted suicide.”[39] In September 2017, the American College of Physicians, which claims more than 150,000 members spread throughout 145 countries, reaffirmed their opposition to physician-assisted suicide, saying, “It is problematic given the nature of the patient–physician relationship, affects trust in the relationship and in the profession, and fundamentally alters the medical profession’s role in society.” They called, “for efforts to address suffering and the needs of patients and families, including improving access to effective hospice and palliative care.” [41]

SPECIFIC PROBLEMS WITH THE END OF LIFE CHOICE ACT 2019

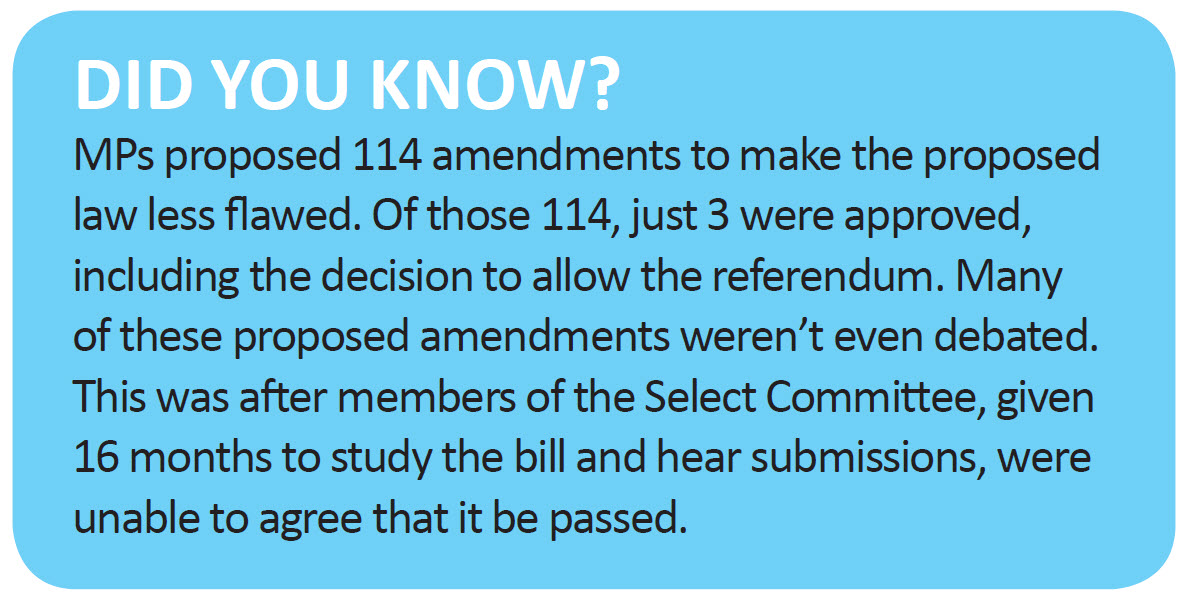

Even if you support some sort of an assisted suicide / euthanasia law, the END OF LIFE CHOICE ACT 2019 is definitely not the solution. The proposed Act contains significant flaws and weaknesses which will place vulnerable and elderly people at risk.

13. No independent witnesses

No independent witnesses are required at any stage of the process, including at the death [s 16]. In contrast, two people need to witness the signing of the written request in Oregon, one of whom must be totally independent (not a relative or someone able to benefit from the estate, or an employee of a health care facility or the attending medical practitioner) [s 2.02]. Canada*[s 241.2 (3)(c)] and Victoria (Aus) [s 34] require two independent witnesses as well as the co-ordinating medical practitioner.

[The majority of MPs voted against requiring an independent witness at the death – SOP 211].

14. No requirement for mental competence at death

There is no safeguard whereby the person’s mental competence to be assessed at the time the lethal dose is administered, which increases the risk of wrongful death. This is not the case in Victoria [s 65] or Canada* [s 241.2(3)(g)-(i)].

15. No cooling-off period

There is no mandatory cooling-off period before the administration of the lethal dose, such as the minimum of 15 days in Oregon [s 3.06][42] (with a recently introduced limited exception), 9 days in Victoria [s 38][43] or 10 days in Canada* [s 241.2(3)(g)]. The only timeframe specified in the End of Life Choice Act 2019 is a minimum of 48 hours between the writing of the prescription and the chosen time of death [s 15(4)], which is also a requirement in Oregon [s 3.08]. That means the whole process from request to death could be completed in just a few days.

[The majority of MPs voted against a one-week cooling-off period – SOP 308 ].

16. No requirement for existing doctor / patient relationship

The first medical practitioner (in the proposed two-practitioner process) need not have met the patient previously. Further, they can also determine a person is eligible for assisted dying without having talked to the person face-to-face. A medical practitioner with concerns could be blocked by the patient from talking to the family to check for coercion. This is especially problematic where a doctor has no former knowledge of the patient. There is no requirement that the person discuss his or her assisted suicide or euthanasia wishes with any other person. These are serious flaws in the Act. Appropriate protections in relation to coercion are sadly lacking. [s 11], [s 3], [s 4], [s 8].

[The majority of MPs voted not to fix these problems – SOP 300, SOP 269].

18. Weak accountability

Under-reporting is a major issue overseas. In the Act we are voting on, the registrar doesn’t need to follow up missing death reports or check for anomalies [s 17(1)(3), s 20(2)]. The review system does not allow for the examination of the patient’s background health records, unlike the Netherlands. And even there, up to a quarter of Dutch euthanasia deaths are not being officially reported. New Zealand could end up with an even less robust system of accountability.

19. No clear line between terminal and chronic / disabled

Supporters of the proposed law claim that it doesn’t threaten people with disabilities. However, many disabilities are life-limiting and involve complications that can become life-threatening. Some chronic conditions can become terminal if the person is refusing treatment [44]. In Oregon “death within six months” has been interpreted by the health authorities to include “death within six months if not receiving medical treatment”.

Supporters of the proposed law claim that it doesn’t threaten people with disabilities. However, many disabilities are life-limiting and involve complications that can become life-threatening. Some chronic conditions can become terminal if the person is refusing treatment [44]. In Oregon “death within six months” has been interpreted by the health authorities to include “death within six months if not receiving medical treatment”.

[An appropriate safeguard was proposed, but MPs didn’t even debate or vote on it – SOP 280].

20. Weak freedom of conscience rights

The Act offers no explicit protection for organisations such as rest homes and hospices whose philosophical, ethical or religious traditions may preclude offering euthanasia or assisted suicide. In the future they may be forced to offer euthanasia on their premises to avoid losing government funding, as has happened in Canada.

The Act offers no explicit protection for organisations such as rest homes and hospices whose philosophical, ethical or religious traditions may preclude offering euthanasia or assisted suicide. In the future they may be forced to offer euthanasia on their premises to avoid losing government funding, as has happened in Canada.

[The majority of MPs voted against putting appropriate protections in this area – SOP 295].

Medical professionals with a conscientious objection would still be obliged to inform the patient about the government body which would be set up to help administer euthanasia, even if this would be against their professional judgment and personal ethics [s 5A, s 6].

[The majority of MPs voted against full freedom of conscience provisions – SOP 299, SOP 209].

* Québec has a different euthanasia law. This footnote applies to points 13, 14 and 15.

Additionally, what has the overseas experience shown us?

Oregon

Oregon

1 in 6 people prescribed lethal drugs under the state’s Death with Dignity Act suffer from clinical depression[45]

Though Oregon doesn’t know the circumstances surrounding the deaths of 543 people who have ingested lethal drugs (about 50% of those who have died under the Death with Dignity Act), in the deaths they do know about, there have been complications in 36 assisted suicide deaths:

- At least 30 people have regurgitated the drugs

- At least 6 have regained consciousness after ingesting the drugs[46]

In 2016, 48.9% of those who died under the Death with Dignity Act cited “burden on family, friends/caregivers” as a reason for accessing assisted suicide[47]

Doctors have prescribed lethal drugs to patients that they have known less than a week. The median length of doctor/patient relations is 13 weeks[48]

Washington (US state)

As of August 2017, one person prescribed lethal drugs in 2009 under the state’s Death with Dignity Act – which requires that those receiving prescriptions have 6 months or less to live – has not died yet. Twenty-two people prescribed lethal drugs in Washington between 2009 and 2017 have not died yet.[57]

Netherlands

Legal euthanasia deaths in the Netherlands:

Legal euthanasia deaths in the Netherlands:

- 54-year-old with personality and eating disorders

- 47-year-old with tinnitus

- A woman in her 70s who had dementia, was secretly drugged and held down by her family while a doctor euthanised her despite her protests that she did not want to die[49]

At least 23% of euthanasia deaths are not reported each year, despite reporting being required by law [50]

When last studied, complications were recorded in 16% of assisted suicide deaths and 6% of euthanasia deaths in the Netherlands[51]

The Netherlands’ Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act was passed in 2002:

- By 2005, newborns could be euthanised under the Groningen Protocol, a list of requirements laid out by the Dutch Society for Paediatrics without recourse to a change in the law by Parliament

- By 2010, reports began coming in of people being euthanised for mental illness in the absence of a physical disease; two such deaths were reported in 2010, rising to 60 deaths by 2016; again, without recourse to Parliament for a change in the law[52]

- In 2012, mobile euthanasia clinics (Levenseindekliniek) began providing euthanasia to patients whose doctors had refused; by 2014, there were 39 of these clinics, again without recourse to Parliament for a change in the law[53]

As of 2016, euthanasia and assisted suicide account for 4.1% of all deaths in the Netherlands – 5,875 euthanasia deaths, and 216 assisted suicide deaths[54]

The country’s highest court has approved euthanasia in cases of advanced dementia. The ruling means doctors cannot be prosecuted even if the patient no longer says or is able to say they want to die. (Apr 2020)

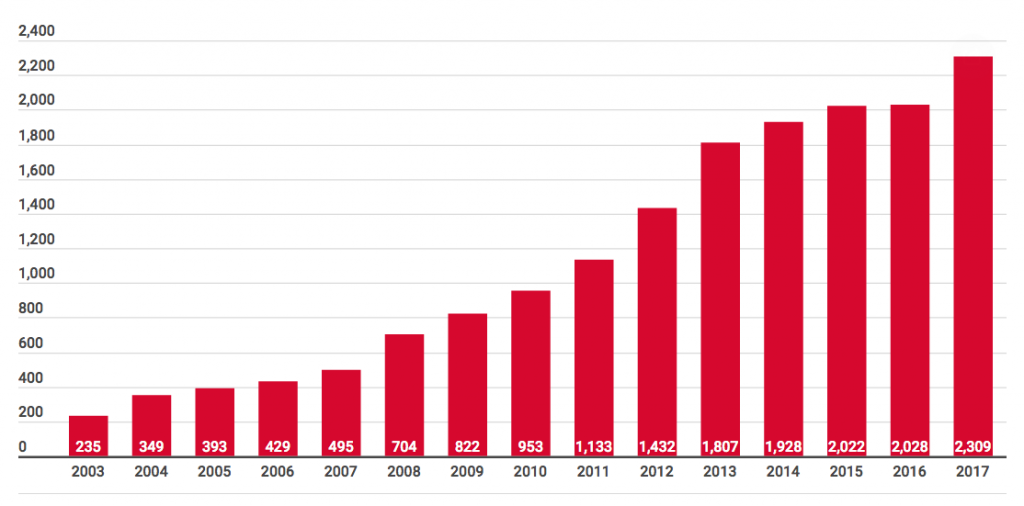

Belgium

Legal euthanasia deaths in Belgium:

Legal euthanasia deaths in Belgium:

- 44-year-old woman with chronic anorexia nervosa

- 45-year-old twins who were going blind

- 24-year-old with depression (cleared for euthanasia, but decided not to go through with it at the last minute)

In the region of Flanders, roughly 30% of all euthanasia deaths are non-voluntary; that’s roughly 1.8% of all deaths in the region[55]

In the Flanders region, approximately 50% of euthanasia deaths are not reported, despite reporting being required by law[56]

Canada

Between June 2016 and June 2017, 1,982 people died under Canada’s Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) Law– 1,977 were euthanised, and 5 people committed assisted suicide[58]

After just one year, pediatricians are already “increasingly” being asked by parents to euthanise disabled or dying children and infants, according to a survey by the Canadian Paediatric Society[59]

Some disturbing cases in the media recently

Dutch court approves euthanasia in cases of advanced dementia Apr 2020

US study says assisted suicide laws rife with dangers to people with disabilities Oct 2019

Dutch Woman With Dementia Euthanized Against Her Will – Doctor Cleared Of Wrongdoing Sep 2019

Kiwi man sentenced for assisted suicides of three disabled people in South Africa June 2019

As a tetraplegic I once supported assisted suicide – but I was wrong (New Zealand) April 2019 (see right)

Canada shows euthanasia soon extended to more than the terminally ill April 2019

Doctors face jail after ‘diagnosing woman with autism so she could get lethal injection’ Nov 2018

Canada gov’t pushes euthanasia ads in hospital waiting rooms Nov 2018

Michigan doctor with cancer planned own death, ‘shocked’ to be alive Oct 2018

Misdiagnosed: A cancer survivor shares her extraordinary tale (New Zealand) Sep 2018

Children are being euthanised in Belgium August 2018

Boy battling cancer wakes from coma as family agree to cut life support August 2018 (see right)

Dylan Asken (UK)

‘Brain-dead’ US boy regains consciousness one day before doctors set to pull plug May 2018

Offered death, terminally ill Ontario man files lawsuit March 2018

Catholic deacon accused of murder by air injection in Belgium Jan 2018

Healthy 29 year-old woman is scheduled to die by euthanasia in the Netherlands Jan 2018

I’m dying of brain cancer. I prepared to end my life. Then I kept living Sep 2017

Terminally ill-groom drops a happy bombshell on his wedding guests – I was misdiagnosed Nov 2017

Canadian Mother says doctor brought up assisted suicide option as sick daughter was within earshot July 2017

Netherlands considers euthanasia for healthy people over 75 July 2017

Terminal cancer patient told hospital would rather spend money on others (New Zealand) Mar 2017 (see right)

Alison and Dion MacKenzie

Woman comes out of coma after doctors tell her mother to turn off life support (New Zealand) Mar 2017

Hospitals slap do-not-resuscitate orders on patients without consent (New Zealand) Feb 2017

Dutch doctor drugged patient’s coffee and got family to hold her down Jan 2017

Dutch gov’t panel: Doctor who forcibly euthanized elderly woman ‘acted in good faith’ Jan 2017

Sex abuse victim in her 20s allowed to choose euthanasia (Holland) Dec 2016

Netherlands offers euthanasia for alcoholics Dec 2016

Assisted-suicide law prompts insurance company to deny coverage to terminally ill California woman Oct 2016

Belgium man seeks euthanasia to end his sexuality struggle June 2016

Sandy Hillburn (UK)

Netherlands sees sharp increase in people choosing euthanasia due to ‘mental health problems’ May 2016

Belgium study finds euthanasia targets women and people with depression or autism July 2015

Woman given two months to live survived for nine years Sep 2016 (see right)

References

[1] Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine (ANZSPM 2013)

[2] Finnis, John (2011b) “Euthanasia and the Law” in his Human Rights and Common Good—Collected Essays: Volume III. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 211: CMA 2007)

[3] Australian and New Zealand Society of Palliative Medicine (ANZSPM 2013). The Double Effect principle was endorsed by the NZ High Court in Seales v Attorney-General [2015] NZHC 1239 at [101]-[106]

[4] Nicklinson v A Primary Care Trust [2013] EWCA Civ 961 at [25] and [26]

[5] Skegg et al 2006: 230, 534

[6] Chambaere, Kenneth, Johan Bilsen, Joachim Cohen, et al (2010) “Physician-assisted deaths under the euthanasia law in Belgium: a population-based survey” Canadian Medical Association Journal 182(9): 895-901 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2882449/

[7] Pretty v DPP [2001] UKHL 61 at [54]

[8] Mark L Graber, “The incidences of diagnostic error in medicine,” BMJ Quality and Safety, 0 (2013): p. 1, http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/qhc/early/2013/08/07/bmjqs-2012-001615.full.pdf.

[9] B Winters, J Custer, SM Galvagno, et al., “Diagnostic errors in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of autopsy studies,” BMJ Quality and Safety 21 (2012): p. 894, http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/21/11/894.

[10] Nicholas A Christakis and Elizabeth B Lamont, “Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study,” BMJ 320 (2000): 469, http://www.bmj.com/content/320/7233/469.

[11] Victoria Reggie Kennedy, “Question 2 Insults Kennedy’s Memory,” Cape Cod Times, November 3, 2012, http://www.capecodtimes.com/article/20121027/OPINION/210270347

[12] Government of the Netherlands, “Euthanasia, assisted suicide and non-resuscitation on request,” https://www.government.nl/topics/euthanasia/euthanasia-assisted-suicide-and-non-resuscitation-on-request.

[13] Kira Brekke, “Dutch Doctors Urge Lawmakers To Extend Euthanasia Law to Children,” Huffington Post, 2015, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/24/netherlands-right-to-die_n_7645676.html.

[14] Rory Watson, “Belgium extends euthanasia to children,” BMJ, 348 (2014): g1633, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1633.

[15] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2686711/Dont-make-mistake-As-assisted-suicide-bill-goes-Lords-Dutch-regulator-backed-euthanasia-warns-Britain-leads-mass-killing.html

[16] Graham, Hannah and Jeremy Prichard (2013) Voluntary Euthanasia and “Assisted Dying” in Tasmania: A Response to Giddings and McKim. http://bestcare.com.au/index.php/studies/68-voluntary-euthanasia-and-assisted-dying-in-tasmania-a-response-to-giddings-mckim-hannah-graham-jeremy-prichard: 15

[17] Richmond, David (2013) “Why elderly should fear euthanasia and assisted suicide” Euthanasia-Free NZ, 16 June 2013: http://euthanasiadebate.org.nz/84/

[18] Apkarian, A Vania, Yamaya Sosa et al (2004) “Chronic pain patients are impaired on an emotional decision-making task” Pain 108: 129-136

[19] Heath, Iona (2012) “What’s wrong with assisted dying” British Medical Journal 344: e 3755

[20] Health and Sport Committee, “Stage 1 Report on Assisted Suicide (Scotland) Bill,” The Scottish Parliament, SP Paper 712, 2015, Sections 277-280, http://www.parliament.scot/S4_HealthandSportCommittee/Reports/her15-06w-rev.pdf.

[21] https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/read-the-journal/all-issues/2010-2019/2012/vol-125-no-1362/editorial-beautrais

[22] Mishara, Brian L and David N Weistubb (2013) “Premises and evidence in the rhetoric of assisted suicide and euthanasia” International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 26: 427-435

[23] http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/66904738/disability-rights-group-concerned-over-voluntary-euthanasia

[24] United Kingdom Parliament, “Assisted Dying Bill (HL),” House of Lords Hansard, 755, 2014, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/201407-18/debates/14071854000545/AssistedDyingBill(HL).

[25] http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2015/03/always-care-never-kill-how-physician-assisted-suicide-endangers-the-weak-corrupts-medicine-compromises-the-family-and-violates-human-dignity-and-equality

[26] Naftali Bendavid, “For Belgium’s Tormented Souls, Euthanasia-Made-Easy Beckons,” The Wall Street Journal, June 14, 2013, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323463704578495102975991248

[27] Editorial, “Belgian Helped to Die After Three Sex Change Operations,” BBC News, October 2, 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-24373107

[28] Graeme Hamilton, “Death by Doctor: Controversial Physician Has Made His Name Delivering Euthanasia When No One Else Will,” National Post, November 22, 2013, http://news.nationalpost.com/2013/11/22/death-by-doctor-controversial-physician-has-made-his-name-delivering-euthanasia-when-no-one-else-will/

[29] DutchNews.nl, “Woman, 70, Is Given Euthanasia After Going Blind,” October 7, 2013, http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2013/10/women_70_gets_euthanasia_after/

[30] DutchNews.nl, “Euthanasia Clinic Criticized for Helping Woman with Severe Tinnitus to Die,” January 19, 2015, http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2015/01/euthanasia-clinic-criticised-for-helping-woman-with-severe-tinnitus-to-die.php/

[31] Joke Mat, “In the Netherlands, Nine Psychiatric Patients Received Euthanasia,” NRC Handelsblad (Amsterdam), January 2, 2014, http://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2014/01/02/in-the-netherlands-nine-psychiatric-patients-received-euthanasia/

[32] Dr John Fox, “Assisted suicide devalues the disabled,” The Spinoff, 2017, https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/18-07-2017/assisted-dying-devalues-the-disabled/.

[33] Aaron J. Trachtenberg and Braden Manns, “Cost analysis of medical assistance in dying in Canada,”CMAJ 23, 189 (2017):E101-5, http://www.cmaj.ca/content/189/3/E101.full.pdf+html.

[34] Susan Donaldson James, “Death Drugs Cause Uproar on Oregon,” ABC News, 2008, http://abcnews.go.com/Health/story?id=5517492&page=1

[35] Mishara and Wiesstubb 2013: 434

[36] See Seales v Attorney-General [2015] NZHC 1239 at [56]-[57]

[37] New Zealand Medical Association, “Submission to End of Life Choice Bill” 2018 https://global-uploads.webflow.com/5e332a62c703f653182faf47/5e332a62c703f6078a2fd218_NZMA%20Submission%20on%20End%20of%20Life%20Choice%20Bill%20FINAL.pdf

[38] World Medical Association, “WMA Resolution on Euthanasia,” 2019, https://www.wma.net/news-post/world-medical-association-reaffirms-opposition-to-euthanasia-and-physician-assisted-suicide/

[39] ANZSPM, “Position Statement: The Practice of Euthanasia and Physician Assisted Suicide,” 2017, http://10questionsfordavidseymour.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/ANZSPM-Position-Statement-2013-on-The-Practice-of-EuthanasiaAssisted-Suicide.pdf.

[40] http://www.nzma.org.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/16996/Euthanasia-2005.pdf

[41] http://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/2654458/ethics-legalization-physician-assisted-suicide-american-college-physicians-position-paper

[42] Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act has been changed to allow for the mandatory 15-day waiting period to be waived if a person is expected to die within this period. It is due to come into effect on 1 January 2020. See https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2019R1/Measures/Overview/SB579

[43] In Victoria the waiting period does not apply if the person is likely to die before the expiry of the time period [s 38].

[44] For example: Claire Freeman is a tetraplegic who would be terminal with weeks to live if she would refuse the cares and treatments that are keeping her alive. https://www.defendnz.co.nz/claire. Kylee Black has a longstanding degenerative genetic condition that is also a disability and, in her case, life-limiting. https://www.defendnz.co.nz/kylee

[45] BMJ (2008); Journal of Medical Ethics (2011)

[46] Oregon Public Health Division, Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act: 2016 data summary (2017).

[47] Oregon Public Health Division, Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act (2017).

[48] Oregon Public Health Division, Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act (2017).

[49] Dutch News, “Doctor reprimanded for ‘overstepping mark’ during euthanasia on dementia patient,” (29 January 2017), available at: http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2017/01/doctor-reprimanded-for-overstepping-mark-during-euthanasia-on-dementia-patient/.

[50] B D Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., “Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: a repeated cross-sectional survey,” in Lancet (2012) 380(9845): 908-915.

[51] JH Groenewoud, et al., “Clinical problems with the performance of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the Netherlands,” in New England Journal of Medicine (2000) 342(8): 551-6.

[52] S Boztas, “Netherlands sees sharp increase in people choosing euthanasia due to ‘mental health problems’,” in The Telegraph (11 May 2016); SYH Kim, RG De Vries, J Peteet, “Euthanasia and assisted suicide of patients with psychiatric disorders in the Netherlands 2011 to 2014,” in JAMA Psychiatry (2016) 73(4): 362-368.

[53] M C Snijdewind, D L Willema, L Deliens, et al, “A study of the first year of the End-of-Life Clinic for physician-assisted dying in the Netherlands,” in JAMA Internal Medicine (2015) 175:10, 1633-1640.

[54] European Institute of Bioethics, “Netherlands 2016 euthanasia deaths increase by another 10%,” (18 April 2017), available at: https://www.ieb-eib.org/fr/pdf/report-2016-euthanasia-in-netherlands.pdf.

[55] Canadian Medical Association Journal (2010)

[56] BMJ (2010)

[57] Washington State Department of Health, “2016 Death with Dignity Act Report” (2017), available at: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct2016.PDF.

[58] Health Canada, “2nd Interim Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada,” (2017), available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/health-system-services/medical-assistance-dying-interim-report-sep-2017.html.

[59] https://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/medical-assistance-in-dying#ref22

[60] https://www.parliament.nz/resource/en-NZ/PAP_74858/f9d96acc7a874d8f2709a40bb20cdb2c8d5548b5

[61] Kastenbaum, Robert (2006) The Psychology of Death, 3rd ed. New York: Springer; Mishara and Weisstub 2013: 433

[62] H. M. Chochinov et al., “Desire for Death in the Terminally Ill,” The American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 152, No. 8 (August 1995), pp. 1185–1191

[63] Herbert Hendin and Kathleen Foley, “Physician-Assisted Suicide in Oregon: A Medical Perspective,” Michigan Law Review, Vol. 106, No. 8 (June 2008), p. 1622

[64] Hendin and Foley, “Physician-Assisted Suicide in Oregon,” pp. 1625–1626

AUTHORISED BY FAMILY FIRST NZ, 28 DAVIES AVE, MANUKAU CITY 2241